on Tuesday April 20, 2021

Interview with MLA+ on Sustainable Urban Planning

Did you know that cities produce about 72% of the global greenhouse gas emissions? Such numbers raise the question if cities can be designed in a way to fight climate change instead of boosting it. Read this interview to learn how urbanists approach municipalities and developers for putting forward their sustainable solutions.

According to reports, humanity needs to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to keep the global temperatures rising to a maximum of 1.5°C per century. This is believed to be the point of no return for our planet, so our actions have to be fast and precise. Most of these actions must affect cities since they produce about 72% of the global greenhouse gas emissions. The cities, being a platform for education, science, and innovation, simultaneously remain a crucial source of overconsumption and pollution. Can we design and administer urban environments in a way that would fight climate change instead of boosting it?

One of Orange Bird Agency’s little birds was lucky enough to grab a cup of coffee with a spatial expert Mikhail Stepura and ask him this and other questions. Mikhail works at an international urban planning office MLA+ and shares his vision on sustainable cities in this interview.

Please, say a few words about your expertise and role at MLA+.

My name is Mikhail Stepura, and I play multiple roles in our company. I have a degree in architecture and develop urban planning projects and territorial development projects.

How concerned are you personally and MLA+ in general with climate change? Do you take it into account in your urban planning projects? How would you describe a sustainable city in several sentences?

When I met the term “sustainable development” in the literature for the first time, it meant a kind of development that required minimal human, economic, and time resources at each stage of its existence. Regarding the building environment, this means a design stage, a construction stage, and a functioning stage of the project. Importantly, sustainability includes a rational use of city territories, which is one of our aims. Today, many of our customers, mostly municipalities of the cities, reach MLA+ and ask us to develop strategic plans for large territories. Our mission in such projects is to reconstruct the existing building environments and prevent sprawling to the empty remote land plots. Therefore, densification is one of our central ideas linked to sustainability.

Your work is mostly focused on the development of blue/green infrastructure in the cities – parks, waterfronts, coastal areas, etc. What made you interested in designing such spaces? What is their role in urban ecosystems?

That is true. You see, our staff is very young. The young colleagues of mine say that working at MLA+ is interesting, projects are challenging, and the office atmosphere is pleasant, so many people apply for internships.

A couple of years ago, together with the interns, we developed research on Saint-Petersburg where one of MLA+’s offices is located. We studied the city’s capacity, the number of buildings the inner city can accommodate without the sprawl, building up the underused peripheral territories. The numbers turned out to be amazing! We discovered that it is possible to keep densifying the city itself for the next 14-15 years while constructing the same amount of buildings as is being built today. We exhibited this project in Saint-Petersburg, at the festival Zodchestvo 2019, and then at the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism. This experience inspired our team to continue the format of a laboratory with the participation of our interns.

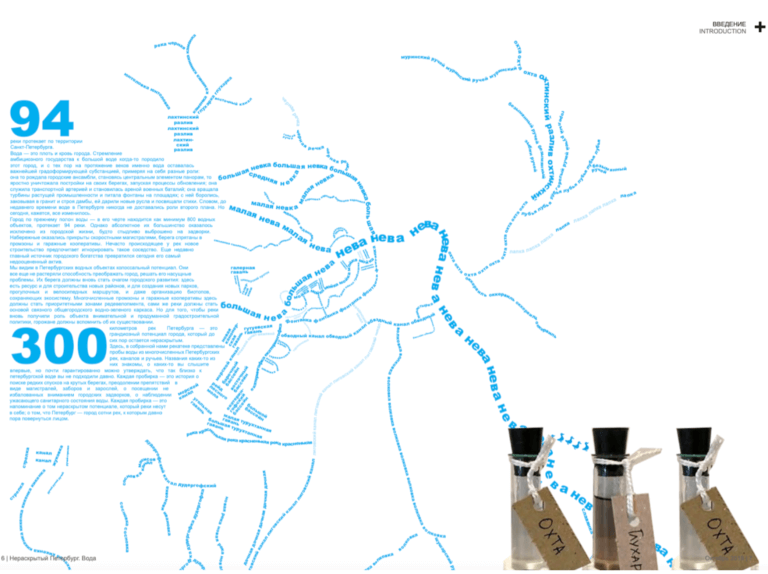

Image 1. Excerpt from the water study of Saint Petersburg by MLA+ . The map depicts rivers flowing throughout the city, with water samples taken from these rivers at the bottom right. Source: MLAplus.com

Image 1. Excerpt from the water study of Saint Petersburg by MLA+ . The map depicts rivers flowing throughout the city, with water samples taken from these rivers at the bottom right. Source: MLAplus.com

We started to think of a new topic and realised that we wanted to react to or, probably, even set a contemporary agenda. That is how a Water Laboratory appeared. In Saint-Petersburg, there is so much water, yet people do not use it. In the central city, along the rivers, there are granite waterfronts built before the twentieth century. Another category represents the riverfronts in the industrial areas and they, as a rule, are not available to the public at all. Finally, we found several nice rivers surrounded by greenery in the peripheral parts of the city. Once we identified the issue, we decided to evaluate the blue/green infrastructure of the city and to suggest ways for its improvement. We did this work for creating a comprehensive strategy for riverfront development so the municipality has a tool, a set of requirements for the private developers in the future.

According to the latest data, the building industry is responsible for nearly 40% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. What is our responsibility as spatial experts in decreasing these numbers? What can urban planners and architects do for decreasing them drastically?

My answer may be predictable, yet one of the largest sources of pollution is transportation. If we decrease the use of private cars in the cities, we will affect the environment significantly. To achieve that, we need to develop public transportation and the concept of a compact city in general. In a compact city, people prefer walking, riding a bike or a scooter, which is getting more and more popular. That is one of the directions of our work. We try to convince municipalities to encourage the use of public transportation and make the use of a private car, by contrast, more challenging. In large cities we see that users have switched their focus on public transport, carsharing, e-vehicles. Another tool, even more important for me as an urban planner, is a rational placement of residential areas and workplaces. Designing mixed-use neighborhoods where citizens can both live and work would also reduce the need for cars. If we take these steps now, we will cut our emissions drastically.

What customers do you usually work for? How do you communicate the importance of sustainable solutions to them? Do you approach customers from the public and private sectors differently?

We have two main groups of customers. The first one includes private customers, as a rule, a developer who wants to build a residential area. We work with different scales from one building or a block to large territories around 60-70 ha. Another group is municipalities, administrations of the cities. Here, we also work with different formats – concepts of territorial development and master plans.

I may be wrong, though for the first group, developers, environmental sustainability is not a very attractive concept. They might be aware of its importance, yet their aim is profit. They are mostly interested in building quite an effective project with an attractive design and spacious apartments for increasing sales. Start quickly, build quickly, sell quickly – and move to the next project. Such an approach is understandable. However, some private customers understand that competition in the market is getting more severe, and they have to offer new formats of dwellings. This is the moment when an ecological agenda becomes important. Additionally to the apartments, developers start offering eco-friendly comfortable urban settings, green territories nearby, and maintenance of these facilities.

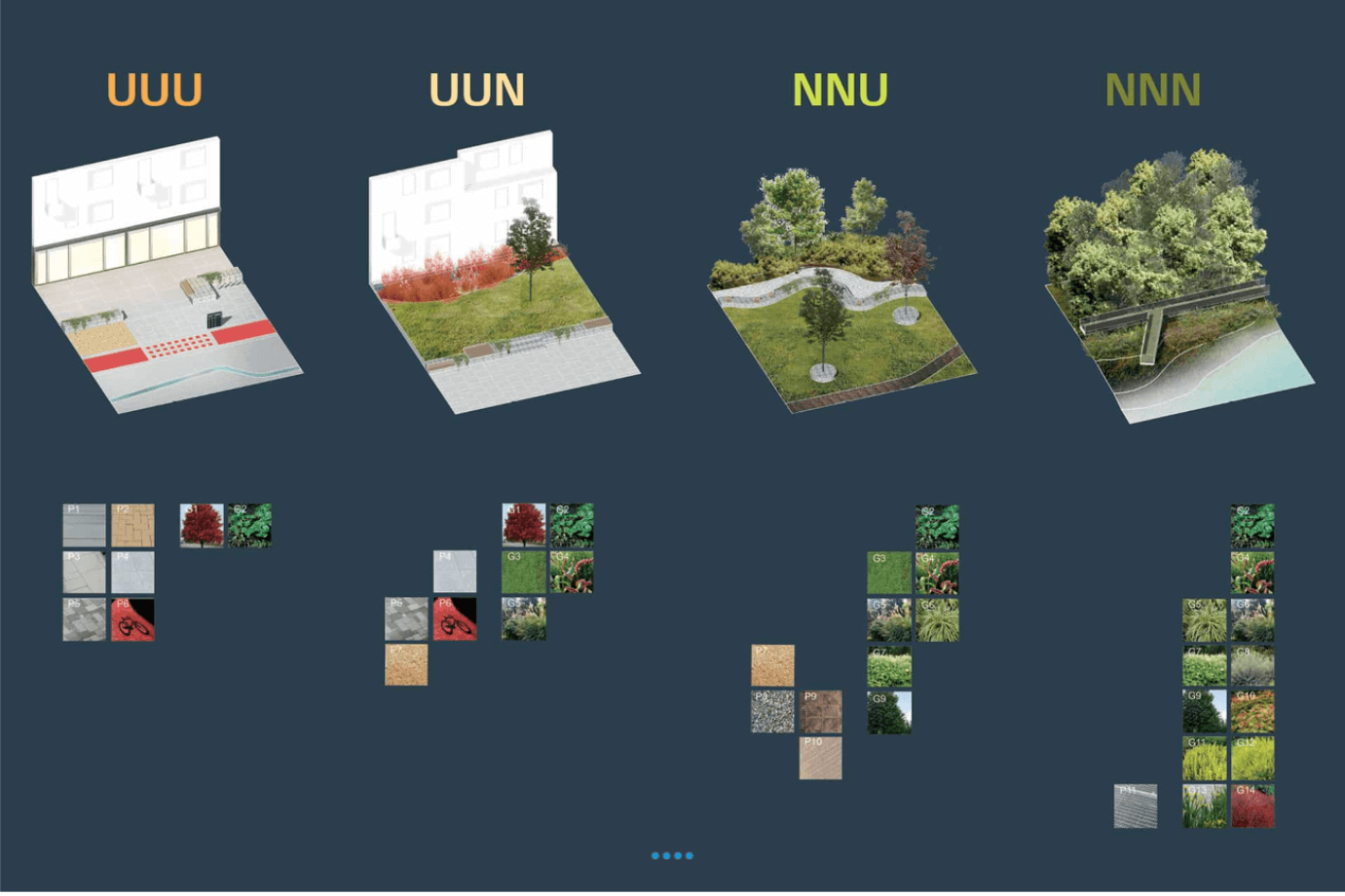

Image 2: Public spaces design concept of a residential area in Moscow by MLA+. Each of the four zones is given the appropriate design code for the surface materials, plants and equipment used in these areas throughout the project. Source: MLAplus.com

Image 2: Public spaces design concept of a residential area in Moscow by MLA+. Each of the four zones is given the appropriate design code for the surface materials, plants and equipment used in these areas throughout the project. Source: MLAplus.com

An example to illustrate this: MLA+ was developing a strategy for quite a large residential area in Moscow. For this project, we designed a specific approach. We divided the territory into around ten zones with code names. The most urbanized one was called 3U, or urban-urban-urban. The one where most of the existing landscape was preserved we called 3N, or nature-nature-nature. Between them, we placed the zones with a different balance of natural and designed environments. For our customer, it was a clear idea. The developer had a budget and, instead of spreading it on the whole territory, they invested in chosen zones differentially. The zone where nature remained untouched cost nothing, while the zone closest to the bus stops or other urban infrastructure was the most expensive. Besides, maintenance costs turned out to be different. 3N zones compounded around 50% of the territory and did not require much work, whereas highly urbanized zones (20-30%) were carefully maintained. Such a system is cheaper than cutting the grass or removing fallen foliage in the entire neighborhood equally.

Coming back to your work with municipalities, what determines the degree to which a municipality is open for sustainable solutions and is willing to create a sustainable city? What would you recommend to cleantech companies, who offer technologies and products for making our cities sustainable but cannot convince municipalities how urgent such solutions are?

I would say that people who work in municipalities are rather different. Forward-looking officials want to change their cities and tend to seek new information and new approaches. Such teams visit urban forums or educate themselves on other platforms and want to make their cities more comfortable and liveable. They approach us, so we share our knowledge in this area, often thanks to our previous projects or recommendations.

While working with municipalities in Russia, sometimes we have to articulate the basic ideas. Our team explains why building up the empty plots outside of the city is not reasonable. We refer to the budgets by arguing that transport and engineering infrastructures in peripheral areas would be expensive, and the municipality can spend this money on inner-city development instead. Such reasoning usually persuades the officials, and they agree with the proposed ideas for further action.

Our office in Rotterdam, on the other hand, has a rather different experience. One of their projects has started with an open call from the Dutch government. It initiated a program called Water as Leverage that aimed at exploring different approaches to water management in Asia. Three shortlisted cities, Chenay in India, Khulna in Bangladesh, and Semarang in Indonesia, have similar urgent problems – urbanisation, flooding, severe weather changes. Before starting the project in these cities, the working group had conversations with the local administrations to understand whether they would support a program like that. Therefore, planners did not have to convince anyone that the project was necessary, this was a high-level policy work of the Dutch government.

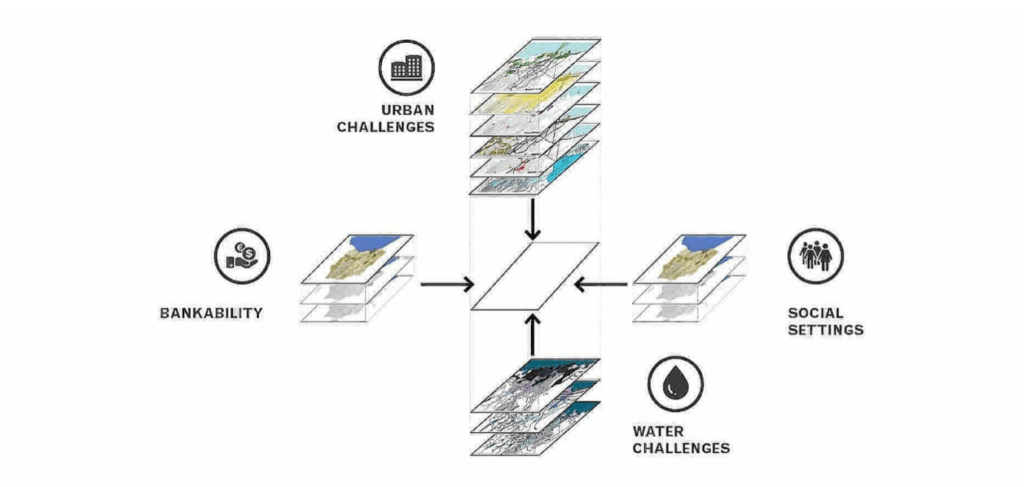

Image 3. The four key challenges for a successful Water as Leverage project by MLA+. Source: MLAplus.com

Image 3. The four key challenges for a successful Water as Leverage project by MLA+. Source: MLAplus.com

As my colleague Markus Appenzeller described, to have enough support, right from the start they involved all the relevant local stakeholders. They reached politicians, of course, but also the local university played a significant role in advocating their design solutions. For presenting the ideas to the public, planners put the local actors in the spotlight. They also had a series of workshops with the representatives of local groups and infrastructural organizations like, for instance, the water supply company or the sewage treatment agency. Working together with the community helps to show that the proposal is much more their thing than something that comes from above. If such a project is not rooted and does not have local support, there is no way to achieve anything. That is probably true everywhere in the world*.

So, appealing to financial aspects and involving local stakeholders turn out to be effective, don’t they? To sum up, what would you call a key to an effective collaboration with municipalities: being persistent, continuing the dialogue, giving this process some time?

A bit of all. I cannot say that our experience with municipalities consists of victories exclusively. We came, and they immediately moved in the right direction – no, it does not work like that. I would emphasise the role of education in this sense. We have to plant the seeds of new progressive ideas so they grow in the future.

*Special thanks to Yana Golubeva and Markus Appenzeller for their comments.

Previous postNext post